Even Robinson Crusoe Understood The Price And Value Of Money

Nothing is as crucial to the functionality of a free market as its money. Money constitutes half of every transaction, representing one side of all value expressed in the exchange of goods and services. But what, exactly, is the price of money?

The commodity with the highest marketability tends to become a society’s preferred medium of exchange — that is, its money. Prices denominated in this common medium enable economic calculation, which in turn allows entrepreneurs to spot opportunities, make profits and push civilization forward.

We’ve seen how supply and demand determine the price of goods, but determining the price of money is a bit trickier. Our predicament is that we have no unit of account to measure the price of money because we already express prices in… you guessed it, money. And because we cannot use monetary terms to explain it, we must find another way to express money’s purchasing power.

People buy and sell money (exchange goods and services for it) based on what they expect that money will buy them in the future. As we’ve learned, acting individuals always make choices on the margin. Hence, the law of diminishing marginal utility. In other words, all actions are preceded by a value judgment in which actors choose between their most valued end and their next strongest desire. The law of diminishing marginal utility applies here as it does elsewhere: the more units of a good a person possesses, the less urgent the satisfaction each additional unit provides.

Money behaves no differently. Its value lies in the additional satisfaction it can provide. Whether that’s buying food, security or future options doesn’t matter. When people trade their labor for money, they do so only because they value the purchasing power of that money more than the immediate use of their time. The cost of money in an exchange is thus the highest utility a person could have derived from the amount of cash they gave up. If a person chooses to work for an hour to afford a rib-eye steak, they must value the meal more than one hour of forgone leisure.

Recall that the law of diminishing marginal returns tells us that each successive unit of a homogenous good satisfies a less urgent desire a person has. Therefore, the value a person attaches to an additional unit diminishes for each unit added. However, what constitutes a homogenous good is entirely up to the individual. Since value is subjective, the utility of each additional monetary token depends on what the individual wants to achieve. To the individual, each extra token is not homogenous in terms of what serviceability it brings to them. To a person who wishes to buy nothing but hot dogs with his money, a “unit of money” is the same as whatever the price of a hot dog is. That person has not added a unit of the homogenous good “money for hot dogs” until he has acquired enough cash to buy one more hot dog.

This is why Robinson Crusoe could look upon a pile of gold and deem it worthless. It couldn’t buy him food, tools or shelter. In isolation, money is meaningless. Like all languages, it requires at least two people to function. Money, above all, is a tool for communication.

Inflation and the Illusion of Idle Money

People choose to save, spend, or invest based on their time preference and their expectations about money’s future value. If they expect purchasing power to increase, they’ll save. If they expect it to fall, they’ll spend. Investors make similar judgments, often redirecting money toward assets they believe will outpace inflation. But whether saved or invested, money is always doing something for its owner. Even money “on the sidelines” serves a clear purpose: lowering uncertainty. A person who holds onto money instead of spending it is satisfying their desire for optionality and safety.

This is why the idea of money “in circulation” is misleading. Money does not flow like a river. It is always held by someone, always owned, always performing a service. Exchanges are actions, and actions happen at specific points in time. Therefore, there is no such thing as idle money.

Without its connection to historical prices, money would be unmoored, and personal economic calculation would be impossible. If a loaf of bread cost $1 last year and costs $1.10 today, we can infer something about the direction of purchasing power. Over time, these observations form the basis for economic expectations. Governments offer their own version of this analysis: the Consumer Price Index (CPI).

This index is supposed to reflect the “rate of inflation” through a fixed basket of goods. However, CPI deliberately ignores high-value assets like real estate, stocks, and fine art. Why? Because including them would reveal a truth governments would rather hide: Inflation is always far more pervasive than the people behind it admit. Measuring inflation through CPI is an attempt to hide the when-you-really-think-about-it obvious truth about it: The increase in prices is always proportional to the expansion of the money supply eventually. The creation of new money always leads to a decrease in the purchasing power of that money compared to what it could have been.

Price inflation is not caused by greedy producers or supply-chain hiccups. It is always, eventually, the result of monetary expansion. When more money is created, its purchasing power falls. Those closest to the source of new money benefit (banks, asset holders and state-connected companies and corporations), while the poor and wage-earning class bear the brunt of price increases.

The effects are delayed and are difficult to trace directly, which is why inflation is often called the most insidious form of theft. It destroys savings, widens inequality and increases financial instability. Ironically, even the wealthy would be better off under a sound monetary regime. In the long run, inflation harms everyone. Even those who appear to benefit in the short term.

The Origins of Money

If money’s value comes from what it can buy, and if that value is always judged against past prices, how did money acquire its initial worth? To answer this, we must look backward to the barter economy.

The good that evolved into money must have had nonmonetary value before it became money. Its purchasing power must initially have been determined by the demand for some other use case. Once it began serving a second function (as a medium of exchange), its demand increased, and so did its price. The good now served two distinct purposes for the owner: providing utility value on the one hand and functioning as a medium of exchange on the other. The need for the latter use case tends to overshadow the former over time.

This is the core of Mises’ Regression Theorem, which explains how money arises naturally in markets and always retains a link to past valuations. It is not an invention of the state but a spontaneous outgrowth of voluntary trade.

Gold became money because it met the criteria of being a good money: It was durable, divisible, recognizable, portable and scarce. Its use in jewelry and industry still gives it use-value today. For centuries, banknotes were mere receipts redeemable for gold. The lightweight and compact banknote proved the perfect solution to gold’s transportability problem. Unfortunately, the issuers of these receipts quickly realized they could issue more gold tickets (banknotes) than they had backing for in their vaults. This modus operandi is still in use today.

Once the link between gold and banknotes was severed altogether, governments and central banks were free to create money ex nihilo, leading to today’s unbacked fiat systems. Under fiat regimes, politically connected banks can be bailed out, even if they fail. The result is moral hazard, distorted risk signals, and systemic instability, all funded by the quiet expropriation of savings through inflation.

Money’s temporal connection to historical prices is vital for the market process. Without it, personal economic calculations would be impossible. The Money Regression Theorem, described in the previous section, is a praxeological insight often overlooked in discussions about money. It explains why money is not just an imaginary construct by some bureaucratic wizardry but has a real connection to a point when someone’s desire to trade means for a specific end spawned it into existence in the free market.

Money is a product of voluntary exchange, not a political invention, a shared illusion, or a social contract. Any commodity with a limited enough supply could be used as money, presuming it ticked off all the other boxes necessary for a suitable medium of exchange. Anything durable, portable, divisible, uniform, and acceptable will do.

Suppose the Mona Lisa had been infinitely divisible. In that case, its parts could have served as money, but only if there was an easy way to verify that they were actually from the Mona Lisa and not counterfeited.

Speaking of the Mona Lisa, there’s an anecdote about some of the most famous painters of the twentieth century that perfectly illustrates how an increase in the supply of a monetary good affects its perceived value. These painters realized they could use their celebrity status to enrich themselves in a peculiar way. They figured out that their signatures were valuable and that they could pay their restaurant bills by simply signing them. Salvador Dali allegedly even signed the wreck of a car that he had crashed into and thus magically transformed it into a valuable piece of art. Eventually, though, these tactics stopped working. The more signed bills, posters, and car wrecks there were, the less valuable an additional signature became, perfectly demonstrating the law of diminishing returns. By adding quantity, they reduced quality.

The World’s Largest Pyramid Scheme

Fiat currencies operate under similar logic. Increasing the money supply devalues each existing unit. While the early recipients of new money benefit, everyone else suffers. Inflation is not just a technical issue but a moral one, too. It distorts economic calculation, rewards debt over savings, and robs those least able to defend themselves against it. In this light, fiat currency is the world’s largest pyramid scheme, enriching the top at the expense of the base.

We accept broken money because it’s what we’ve inherited, not because it serves us best. However, when enough people realize that sound money (money that can’t be counterfeited) is better for the market and humanity, we may stop settling for fake gold receipts that cannot feed us and start building a world where value is real, honest and earned.

Sound money arises through voluntary choice, not political decree. Any item that satisfies the basic criteria of money can serve as money, but only sound money allows civilization to flourish long-term. Money is not merely an economic tool but a moral institution. When money is corrupted, everything downstream — savings, prices incentives and trust — is distorted. But when money is honest, the market can coordinate production, signal scarcity, reward thrift, and protect the vulnerable.

In the end, money is more than a means of exchange. It is a safeguard of time, a record of trust, and the most universal language of human cooperation. Corrupt that, and you don’t just break the economy. You break civilization itself.

“Man is a short-sighted creature, sees but a very little way before him, and as his passions are none of his best friends, so his particular affections are generally his worst counselors.”

Counterfeiting: Modern Money and the Fiat Illusion

Now that we’ve explored how a saleable good becomes money on the free market and how low-time-preference thinking leads to progress and falling prices, we can take a closer look at how money functions today. You may have heard about negative interest rates and

wondered how they square with the fundamental principle that time preference is always positive. Or perhaps you’ve noticed rising consumer prices, with media outlets blaming

everything but monetary expansion.

The truth about modern money is a hard pill to swallow because once you understand the magnitude of the problem, things start looking pretty bleak. Human beings cannot resist the urge to enrich themselves by exploiting others through printing money. The only way to prevent this, it seems, would be to remove us from the process altogether, or, at the very least, separate money from state control. Nobel Prize-winning economist Friedrich Hayek believed this could only be done in “some sly, roundabout way.”

The United Kingdom was the first nation to weaken the link between national currencies and gold. Before World War I, nearly all currencies were redeemable in gold, a standard that had emerged over thousands of years as gold became the most saleable good on Earth. However, by 1971, convertibility was abandoned entirely when U.S. President Richard Nixon famously proclaimed he would “temporarily suspend the convertibility of the dollar into gold” and unilaterally severed the final link between the two. He did this (at least partially) to finance the Vietnam War and preserve his political power.

We won’t dive into every detail of fiat currency here, but here’s what matters: State-issued money today is not backed by anything tangible but entirely created as debt. Fiat currency masquerades as money, but unlike actual money (which emerges from voluntary exchange), fiat is a tool of debt and control.

Every new dollar, euro or yuan enters existence when a large bank issues a loan. That money is expected to be paid back with interest. And since that interest is never created alongside the principal, there is never enough money in circulation to repay all debts. In fact, more debt is necessary to keep the system alive. Modern central banks further manipulate the money supply through mechanisms like bailouts, which prevent inefficient banks from failing, and quantitative easing, which adds even more fuel to the fire.

Quantitative easing is when a central bank purchases government bonds by creating new money, effectively trading IOUs for freshly printed currency. A bond is a promise by the government to repay the borrowed money with interest. That promise is backed by the state’s power to tax present and future citizens while you and your heirs are forced to cope with rising prices. The result is a quiet, continuous wealth extraction from productive people through inflation and debt servitude.

Money printing continues under the banner of Keynesian economics — the doctrine that underpins most modern government policies. Keynesians argue that spending is what drives an economy forward and that if the private sector doesn’t keep spending, the government must. Every dollar spent, they claim, adds one dollar’s worth of value to the economy, but this view ignores the reality of value dilution through inflation. It’s Bastiat’s Broken Window Fallacy all over again. Adding zeros adds precisely zero value.

If money printing could actually increase wealth, we’d all own super yachts at this point. Wealth is created through production, planning and voluntary exchange, not by increasing the number of digits on a central bank’s balance sheet. Real progress stems from people trading with others and their future selves by accumulating capital, delaying gratification and investing in the future.

Fiat Currency’s Final Destination

Printing more money doesn’t speed up the market process, but distorts and retards it. Literally. Slow and stupid follows. Ever-decreasing purchasing power makes economic calculation more difficult and slows down long-term planning.

All fiat currencies eventually die. Some collapse via hyperinflation. Others are abandoned or absorbed into larger systems (such as smaller national currencies being replaced by the euro). But before their end, fiat currencies serve a hidden purpose — they transfer wealth from those who create value to those with political proximity.

This is the essence of the Cantillon effect, named after 18th-century economist Richard Cantillon. When new money enters the economy, its first recipients benefit most — they can buy goods before prices rise. Those furthest from the source (ordinary workers and savers) absorb the cost. Being poor in a fiat system is very expensive.

Despite this, politicians, central bankers and establishment economists continue to assert that a “healthy” inflation rate is necessary. They should know better. Inflation does not fuel prosperity. At best, it shifts purchasing power. At worst, it erodes the very foundation of civilization by undermining trust in money, savings and cooperation. The abundance of cheap goods in today’s world was created in spite of taxes, borders, inflation and bureaucracy — not because of them.

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

When left unhampered, we know that the market process tends to deliver better goods at lower prices for more people. That’s what real progress looks like. Interestingly, praxeology isn’t just a tool for critique but a framework for appreciation. Many people grow cynical once they see how deep the dysfunction runs, but praxeology offers clarity: It helps you see how productive people are the real drivers of human flourishing. Not governments. Once you understand this point, even the most mundane forms of labor take on greater meaning. The supermarket cashier, the cleaning staff and the taxi driver all contribute to a system that meets human needs through voluntary cooperation and value creation. They are civilization.

Markets produce goods. Governments, by contrast, tend to produce bads. Catallactic competition, where businesses strive to serve customers better, is the engine of innovation. Political competition, where parties fight to control the state, rewards manipulation, not merit. The most adaptable rise in markets. The most unscrupulous rise in politics.

Praxeology helps you understand human incentives. It teaches you to watch what people do, not just what they say. More importantly, it teaches you to consider what could have been, not just what is. That’s the unseen world, the alternative timelines erased by intervention.

Fear, Uncertainty and Doubt

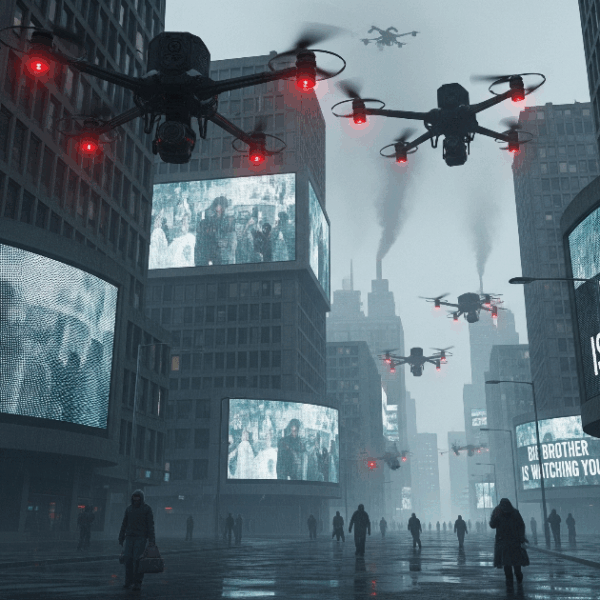

Human psychology is biased toward fear. We evolved to survive threats, not to admire flowers. That’s why alarmism spreads faster than optimism. The proposed solution to every “crisis” — whether related to terrorism, pandemics, or climate change — is always the same: more political control.

Those who study human action know the reason why. For every individual actor, the end always justifies the means. The problem is, this fact is true for power-seekers, too. They offer security in exchange for freedom, but history shows us that fear-driven tradeoffs rarely pay off. When you understand these dynamics, the world becomes clearer. The noise fades.

You turn off the television. You reclaim your time. And you realize that accumulating capital and freeing your time are not selfish acts. They are the basis for helping others.

Investing in yourself — in your skills, savings, and relationships — enlarges the pie for everyone. You participate in the division of labor. You produce value. And you do so voluntarily. The most radical action you can take in a broken system is to build something better outside of it.

Every time you use a fiat currency, you pay its issuers with your time. If you can avoid using them altogether, you help usher in a world with less theft and deceit. It may not be easy, but endeavors worth pursuing rarely are.

Knut Svanholm is a Bitcoin educator, author, armchair philosopher and podcaster. This is an extract from his revamped book Praxeology: The Invisible Hand that Feeds You, published by Lemniscate Media, May 27, 2025.

BM Big Reads are weekly, in-depth articles on some current topic relevant to Bitcoin and Bitcoiners. Opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc or Bitcoin magazine. If you have a submission you think fits the model, feel free to reach out at editor[at]bitcoinmagazine.com.