Rutherford Chang Retrospective: Hundreds And Thousands At UCCA Beijing

When people describe Rutherford Chang’s work, you hear words like: obsessive, conceptual, minimalist. These descriptions aren’t wrong, they point to something real in his practice. But they also miss what makes his approach distinctive. Chang worked with objects that industrial culture designed to be identical: records pressed in millions of copies, portraits drawn according to strict house style, coins minted for perfect interchange. His interest lay in the precise moment when the promise of sameness begins to fail, when time and human handling leave marks that transform supposedly identical objects into singular things.

The retrospective Rutherford Chang: Hundreds and Thousands opened January 17, 2026 at UCCA Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing, one of China’s leading institutions for contemporary art. This exhibition is significant for several reasons. It represents Chang’s first institutional retrospective and his most comprehensive solo presentation to date. It is also a posthumous one. Chang died in 2025 at the age of 45, leaving behind a body of work built almost entirely around the practice of collecting and arranging mass-produced objects until their individual histories became visible and legible.

Beijing provides a fitting location for this retrospective, though not for the obvious reasons alone. Yes, Chang moved frequently between New York and China throughout his career, and yes, he showed work in Beijing early on. But the city itself offers something more specific: a context shaped by rapid cycles of construction and replacement, by the constant acceleration of change and circulation. In such an environment, Chang’s patient attention to what gets left behind, to the residues and traces that accumulate on objects even as they move through systems designed to keep them uniform, takes on particular resonance. The exhibition is co-curated by Philip Tinari, director of UCCA, and Aki Sasamoto, a fellow artist – both longtime friends of Chang who understand his working methods from the inside. Their collaboration keeps the exhibition close to the work as practice, with process and method in the foreground.

To understand Chang’s approach, we need to look carefully at the exhibition’s title. Hundreds and Thousands sounds like simple measurement, like a gesture toward quantification. Chang typically worked at scale. He collected not dozens but hundreds or thousands of examples. But what the title really describes is a method and a particular way of working that emerges when you engage with mass-produced objects at sufficient volume. Chang discovered that quantity, at a certain point, stops behaving in predictable ways. At a certain scale, repetition starts to reveal detail. Put hundreds of nearly identical objects next to each other and you start to see time. You start to see touch. You see accidents. You see storage. You see neglect. You also see care. The marks of individual handling become visible. What you’re looking at, ultimately, is a record of lived life pressed into objects that industrial culture designed to keep stable and interchangeable.

We Buy White Albums

One of Chang’s best-known projects demonstrates this method with particular clarity. We Buy White Albums operates from a constraint simple enough to state in a single sentence, though its implications unfold over years: Chang established a record store that stocked only first pressings of the Beatles’ The Beatles (1968), commonly known as “The White Album”. The store had one rule that inverted normal commercial logic: It sold nothing, it only bought.

This premise is deliberately narrow, and it remains narrow throughout the project’s duration, which turns out to be part of what allows it to scale so effectively over time. During exhibitions where Chang was present, the work functioned in real time: people could show up with their own copy of the White Album and sell it to the archive while the exhibition was on view. The act of buying became a moment of direct exchange between the work and its audience, and the archive grew through these individual transactions instead of curatorial selection or market acquisition. Each copy arrived already marked by years of handling. These marks, the accumulated evidence of circulation, carried the work forward.

To understand why this project works as it does, we need to look more carefully at the White Album itself as an object. Richard Hamilton designed the cover as an almost completely blank white surface. Minimalism at its most reductive form. And yet early pressings carry a stamped serial number, a small detail that complicates the apparent simplicity. This serial number performs a curious double function: it frames each copy as one among many (your copy is number 0234561 out of millions), while simultaneously gesturing toward something like limited edition status through the very act of numbering. Here we find the contradiction built directly into the object itself: mass-produced minimalism making a paradoxical claim to uniqueness. The serial number tells you this is just one copy out of millions, while the blank white cover invites you to make it yours.

Chang understood what this contradiction sets in motion once these objects enter circulation and begin moving through time. The clean white surface that Hamilton designed with such care doesn’t stay clean for long. Everyday life rewrites it. Water damage spreads across the cardboard in irregular patterns. Corners get torn or bent through careless handling or too-tight shelving. Owners write their names on the cover, add notes about when and where they bought the album, sometimes include dedications or detailed lists of favorite tracks. Price stickers from second-hand shops accumulate in layers, creating unintended collages of commercial history. In some cases, mold sets in during storage in damp basements or attics, creating organic patterns that can look almost intentional, or lets say, almost artistic. Through all of this, the album stops being a uniform industrial product and becomes something singular, that’s marked by its particular history.

The decision to collect these albums in any condition and not searching only for pristine, museum-quality copies, represents a choice with significant consequences for how the work means. It means treating damage and wear as information and not as degradation to be corrected or restored. This shift in how we value objects is crucial to understanding the project. A pristine copy might tell you something about careful preservation, about someone who valued the object enough to keep it protected from the world. But a tattered copy, covered in stains and marks, tells a different and probably richer story. In Chang’s hands, these marks remain visible and begin to matter in new ways. He returns again and again, across different projects, to this precise point where objects designed for perfect interchange start to fray at the edges, where they begin to carry their own record of circulation that makes them individually readable.

The work doesn’t stop with physical collection, however. Chang took the project a step further by recording multiple copies of the album and layering them into a single audio piece. One hundred versions of the White Album play simultaneously, drifting gradually out of sync as small differences in quality and accumulated wear compound into a shifting chorus of sound. The result doesn’t register as a remix or a mashup in any conventional sense. It feels closer to the archive itself made audible, a way of hearing how uniformity fails when you stack enough iterations on top of each other. What comes to the surface is not purity or fidelity to an original, but time itself, materialized in the form of friction and noise. The piece functions as what we might call material memory, with surprisingly little interest in fan culture, or the mythology that typically surrounds The Beatles.

The Class of 2008

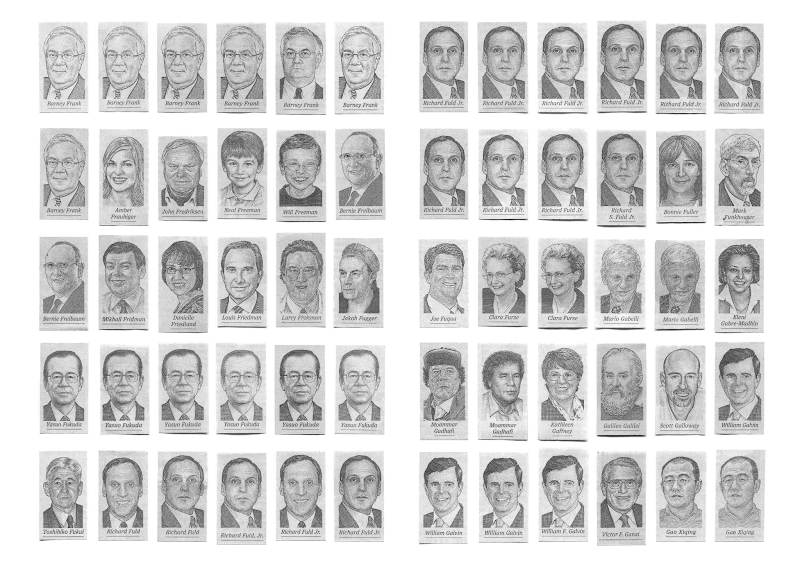

Chang applied this same basic methodological approach to a very different kind of mass-produced object: printed news media. The Class of 2008 presents itself as a straightforward catalogue. It’s an alphabetical listing of every hedcut portrait published in The Wall Street Journal during the year 2008. Before we can understand what Chang does with this material, though, we need to understand what hedcuts are and why they matter. Hedcuts are the distinctive stippled, engraving-style portraits that the Journal uses for certain figures in its reporting. The technique is borrowed deliberately from nineteenth-century engraving, and it carries with it specific associations: authority, permanence, trustworthiness, the visual register of something meant to hold up under scrutiny and stand the test of time.

The structure of the catalogue is deceptively simple: alphabetical order, with repetition kept visible in the record. If someone appeared multiple times in 2008, this is clearly indicated in the book, and those appearances are explicitly not reduced to a single representative entry. This decision about how to organize the material matters, because it allows patterns of repetition and recurrence to emerge through the reader’s encounter with the work. And the timing of the project sharpens its implications considerably. 2008 was, of course as we all know, the year when financial authority came under extraordinary strain, when economic structures that had seemed most stable revealed themselves to be fragile or even illusory. And yet throughout this period, the visual language of legitimacy in the Journal continued without interruption, day after day rendering certain faces in this particular register of authority and trust.

Chang’s catalogue simply records this continuity without adding editorial commentary or explicit critique. The alphabetical organization flattens any narrative arc that the year’s events might suggest. There’s no chronological story being told about crisis and response, no hierarchy of importance imposed through the order of presentation. Instead, repetition itself does the interpretive work. As you page through the book, you notice who appears once and who appears again and again and again. You start to see patterns in who gets rendered in this authoritative visual register and who remains outside it. The hedcut becomes not just a neutral technique of illustration but a question about legitimacy and representation: who gets marked as worth this particular kind of attention, who gets enrolled in this visual vocabulary of permanence and authority, and who remains invisible to this institutional gaze?

Game Boy Tetris

If Chang’s collecting projects make time visible through the gradual accumulation of marks on physical objects, Game Boy Tetris approaches the question of time and repetition through a different medium: labor itself, as the repetitive effort of trying and failing and trying again. The work documents Chang’s repeated attempts to achieve the highest possible score in the original Game Boy version of Tetris, filming the process over an extended period until the accumulation of attempts becomes the substance and meaning of the work. At one point during this extended engagement, he surpassed Steve Wozniak’s score on the leaderboard. A detail he noted with evident satisfaction –– a reminder of how seriously he took questions of record-keeping and documented proof of achievement.

The same simple rule-based system holds your attention through long stretches of concentration punctuated by failure and the decision to restart. The desire for completion, for reaching some definitive endpoint, keeps pulling you back into the loop even as the reasons for continuing become harder to articulate. Progress remains measurable throughout — you can track improvement across attempts, watch skills developing and patterns emerging — even as the larger meaning or purpose of this progress starts to slip away, even as the question of why this particular score matters becomes increasingly difficult to answer with any conviction.

Chang wasn’t observing obsessive cultures or completionist practices from a safe critical distance, making work about collecting or repetition without genuinely participating in those structures himself. Instead, he built systems and constraints that could absorb years of his own attention and effort while still continuing to demand more. Over time, through this sustained and genuine engagement with repetitive structures, Chang himself starts to resemble the thing he’s ostensibly studying. He becomes, in a real sense, a kind of repetitive system himself as lived practice.

CENTS

Chang’s final major project takes his long-standing interest in units, standards, and systems of record-keeping and extends it into what has become an ongoing and in some ways autonomous condition. He completed the physical collection and documentation of ten thousand copper cents in 2023, at a moment when the one-cent coin was still in regular circulation throughout the United States. In 2024 the digital records of these ten thousand individual coins were inscribed onto Bitcoin, allowing the work to continue circulating and accumulating meaning beyond Chang’s direct control or intervention. Then, in a development that gives the entire project an another historical dimension, the U.S. Mint stopped producing the circulating one-cent coin on November 12, 2025. What this means is that in hindsight, with the perspective that historical distance provides, the penny itself has begun to read as a historical object, something that belongs to a particular moment of currency and exchange that is now passing into the past.

The project starts, like most of Chang’s work, from a condition that many people vaguely know about but rarely think through with any care or precision. Chang limited his collection specifically to cents minted before 1982, the year when the U.S. Mint changed the composition of the penny to reduce costs. Before 1982, pennies were made primarily of copper; after that date, they became copper-plated zinc. This seemingly minor detail has real consequences: pennies from the earlier period can, under certain market conditions, exceed their face value when considered purely as raw material. The copper content might be worth more than one cent. This creates an odd situation where the State continues to define each coin as being worth exactly one cent (and makes melting them for their metal content illegal), while the material reality of the object suggests a different value entirely. Chang doesn’t treat this as a paradox to resolve or a problem to solve. He treats it as a given, as one of the structural conditions that makes the work possible and interesting.

The process he developed is methodical and systematic. He removed ten thousand copper cents from circulation, pulling them out of the flow of exchange and use, and documented each one individually through detailed photography (obverse and reverse, better known as heads and tails). The coins were then smelted together into a single copper block weighing sixty-eight pounds. At this moment, individual units disappear entirely into undifferentiated mass. The penny’s ordinary role in exchange, its function as a discrete unit of value that can circulate and combine with other units, comes to a definitive end. But the block itself continues to exist in multiple forms. It was rendered as a detailed 3D digital model and inscribed as a single massive inscription filling the entirety of Bitcoin block #839969. This digital version was then sold at Christie’s in 2024, entering yet another system of value and circulation, moving from material object to digital record to collectible artwork in the contemporary art market.

The documentation, meanwhile, moves in the opposite direction from this consolidation. While the physical coins condense into a single unified object and lose their existence as separable, countable units, each individual cent remains readable as a distinct record. The photographic images stay separate and individuated, each one assigned to a fixed and permanent position in the set through inscription onto individual satoshis. What disappears completely at the level of material form — you can no longer hold these particular ten thousand pennies in your hand, can no longer sort through them or arrange them or put them back into circulation — remains perfectly intact at the level of the record. You can still look at the photograph of each specific coin, still examine the particular wear patterns and surface marks and small imperfections that distinguished it from the nine thousand nine hundred and ninety-nine others.

This structure allows CENTS to hold in tension several different and potentially conflicting ideas about where value is located and how it gets established and maintained. There’s value as defined by governmental authority: the State declares that this coin is worth one cent, and that declaration carries legal force. There’s value registered in material composition: the copper content might actually be worth more than one cent when calculated according to commodity prices. And there’s value produced through preservation and documentation: the decision to photograph each coin individually, to maintain the archive’s legibility over time, to treat these mass-produced objects as worthy of sustained attention. These different registers of value remain distinct within the work, not collapsing into a single unified meaning or resolving into some synthesis.

When we place CENTS alongside We Buy White Albums and think about them as part of a consistent practice, the underlying logic becomes clear. Objects that were designed and manufactured for perfect interchange, for being functionally identical and mutually substitutable, become readable as singular and individual once their circulation is interrupted and held still, once their particular histories are made visible through careful documentation and systematic archiving.

It’s worth noting here — because it matters for understanding how the work continues to function after Chang’s death — that CENTS was initiated through collaboration with Sovrn Art, an independent, artist-first platform that provided the initial framework and support for the project’s development. After the full inscription of the work onto Bitcoin was completed, a council formed independently of Chang himself, without his organization or oversight. This council is made up of collectors who chose, for their own reasons, to take responsibility for the work’s continuation and interpretation. The council members come from different generations and different professional fields, bringing various forms of expertise and perspective to their engagement with the archive. Their work has focused consistently on keeping the distinctions within the archive visible and legible — through close reading of the documentation, through careful cataloguing of variations and patterns, through writing that approaches the material from multiple angles and asks different kinds of questions. Their involvement has centered particularly on the problem of how to keep this archive readable and meaningful over time, how to maintain the precision and care of the record as it continues to circulate through systems and contexts that Chang himself could not have anticipated.

Archive as Practice

It is easy to call Rutherford obsessive. The sustained attention over years, the commitment to completeness and thoroughness, the willingness to spend enormous amounts of time and effort on projects built around deliberately narrow constraints. The word isn’t inaccurate. And yet it still manages to miss something important about the dimension of what Chang was actually doing with his time and attention. He treated mass culture and industrial production with a kind of patience that’s rare in contemporary art. He made rarity and singularity visible inside precisely those things we’ve learned to overlook or dismiss as generic and interchangeable. He listened carefully to what we might call the noise inside familiar symbols and objects — the small variations and accumulated marks that circulation and handling inscribe on surfaces that were designed specifically to resist such marking and remain stable over time.

This attention to what accumulates in the gaps and margins of systems designed for uniformity helps explain why Hundreds and Thousands works so effectively as a title for this retrospective. On one level, it simply names the scale at which Chang characteristically worked: collecting not dozens but hundreds, not hundreds but thousands of examples. But it also names something more fundamental. A discipline, a particular kind of methodical practice that requires looking long enough and carefully enough that difference begins to appear within what first presents itself as sameness. The practice keeps returning, with remarkable consistency across different projects and materials, to what circulation leaves behind: the marks and traces that accumulate even on objects designed to remain stable and unchanged.

Chang’s work can be read, in many ways, as a sustained practice of custody and care. He kept objects, pulled them out of circulation or gathered them from its margins. He indexed and organized them into systems that made their individual histories newly visible and legible. And then, crucially, he returned them to circulation in altered form: as archives open to examination, as exhibitions that invited direct encounter, as permanent records inscribed on Bitcoin. Through this process, he built situations and structures in which circulation itself becomes visible as a process. In which value turns concrete and measurable. The archive is consistently where this transformation takes place in his work — the site and the method through which individual objects become readable as parts of larger systems and patterns.

The retrospective gathers Chang’s method into a single frame and brings together projects from different moments in his career to demonstrate the underlying consistency of his approach across various materials and contexts. What remains is the structure he built, the archives he assembled with such care, the questions he persistently refused to resolve or close down prematurely. The promise of sameness keeps failing. Difference keeps appearing in the gaps and variations. The marks stay visible for anyone willing to look closely enough, and patiently enough, to actually see them.

This is a guest post by Steven Reiss. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc or Bitcoin Magazine.